As if Starmer didn’t have enough problems, his understated response to Siddiq’s situation exposes him to accusations of hypocrisy, given the vituperative way he pursued Boris Johnson for Partygate and then Rishi Sunak for his £60 fixed-penalty fine after being ambushed by Carrie Johnson’s cake. When pursuing Johnson in Parliament in 2022, he said: “The game is up. You cannot be a lawmaker and a lawbreaker and it’s time to pack his bags.“ He also called on Sunak to resign, despite a grovelling apology from the then chancellor.

Starmer’s seeming caution over Siddiq – reportedly a close personal friend – looks somewhat different set against the quick defenestration of Louise Haigh in November, who resigned as transport secretary after it was revealed she had not declared a spent conviction from before she became an MP. This seemed a relatively mild infraction, but Haigh had allegedly alienated allies of the Prime Minister after offering train drivers a 15 per cent pay rise without first clearing it with the Treasury and some believe the scandal was an internal “hit job”.One wonders what Sir Tony Blair makes of Labour’s shambolic approach to communication. He had to let his closest personal ally, Peter Mandelson, resign twice after all. Whatever you think of Blair, his sense of strategy and conviction is what the current Labour leadership appears to so conspicuously lack.

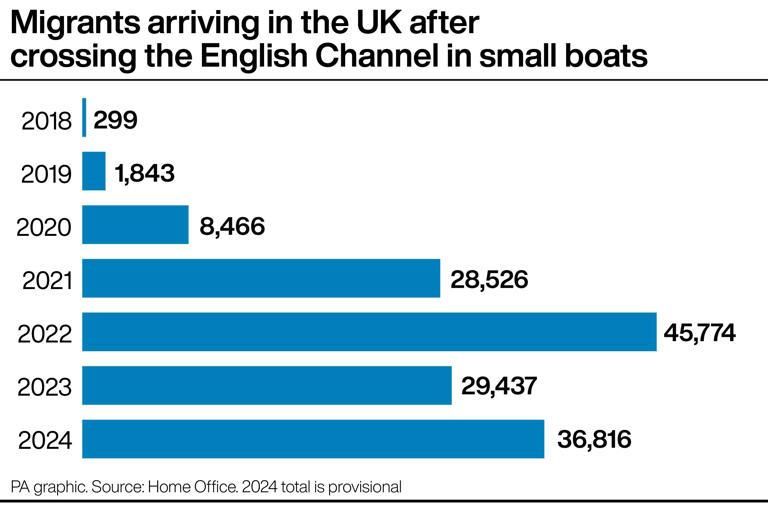

Even if this government has four and half years to go, it feels more like a phantom of Gordon Brown’s dog days than the sunlit uplands of 1997. The sense that our elites do not and cannot understand the struggles of “working people” (let alone those who don’t work) can be traced back to Brown’s awkward encounter with Gillian Duffy in 2010. Brown was trapped by Duffy’s comments over immigration and then was heard to call her “a bigoted woman”. It’s not the substance of the exchange that resonates today, but how it has become a touchstone of the chasm between rulers and ruled, something central to the appeal of Donald Trump in the US, whose populism is likely to influence British politics for at least the next four years.

That Siddiq’s situation is not the big story of the day is down to how Labour are handling their other problems. Aside from upsetting farmers, pensioners, small businesses, big businesses and the armed forces, the Government’s messaging on the grooming gangs scandal has been less than convincing.

Yes, their opponents have seized on this horrific subject opportunistically, but that does not mean there is nothing left to discuss. Portraying the issue as something that the public should move on from seems unwise. The quickest way to facilitate the far-Right is to cede ground for them to move into.

By accusing those calling for a national inquiry of “jumping on a far-Right bandwagon”, Starmer was inadvertently damning anyone calling for an inquiry. This fundamentally misreads or disregards widespread public sentiment. When David Lammy says with exasperation in a radio interview: “We’ve been talking about it for days”, it just reinforces the perception that moving on is more important than facing up. Even if they see this febrile debate as a race to the bottom, admitting it is bad politics.

If they wish to explain why much of the British public is wrong to feel the way it does then fine, explain it so. Be brave. Seize the narrative. Set the agenda. Labour are taking a knife to a gun fight. In another world, in another time, the Siddiq affair would be Labour’s biggest headache. There must be some who wish it was.

Source- Telegraph

.svg)