On a busy lunchtime in Whitechapel, the clatter of plates and low chatter inside a local café masks a deeper conversation — for many British Bangladeshis, thoughts of Bangladesh’s upcoming national election are never far from their minds.

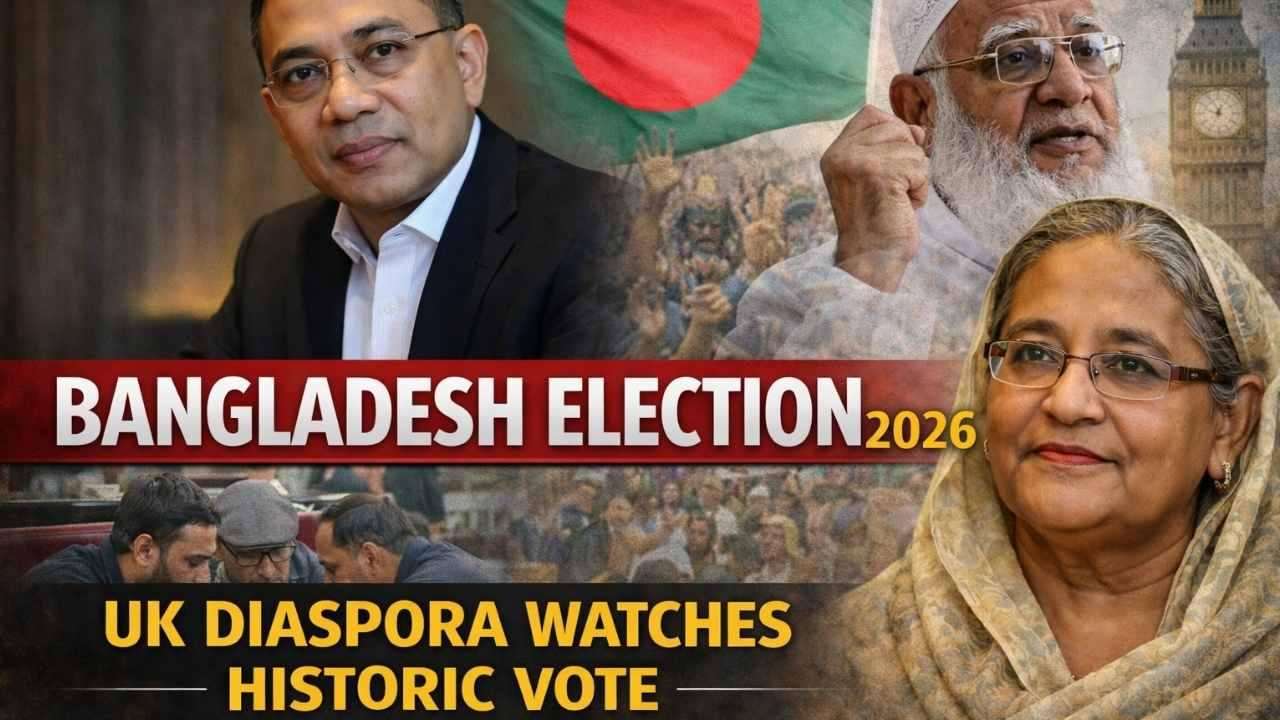

Scheduled for February 12, the vote marks a historic moment. It will be Bangladesh’s first national election since the removal of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina and the first in nearly two decades expected to offer genuine electoral competition. For Bangladeshis living abroad — particularly in the UK — it is also the first time they have been granted the right to vote from overseas.

For months, the election has dominated discussions across East London, home to one of the largest Bangladeshi communities outside South Asia. In Tower Hamlets alone, people of Bangladeshi origin make up around a third of the population.

“This election feels different,” said Khaled Noor, a barrister and political scientist based in London. “For years, people here felt ignored. Now, at least in theory, they have a voice.”

A shift after years of controlled politics

Bangladesh’s political landscape has long been defined by rivalry between the Awami League, led by Sheikh Hasina, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), founded by former military ruler Ziaur Rahman. While Hasina’s rule coincided with strong economic growth, it was also marked by allegations of authoritarianism, repression and tightly managed elections.

The BNP, marginalised for much of the past decade, is now seeking a return to power under the leadership of Tarique Rahman, Ziaur Rahman’s son, who spent 17 years in exile in London. His supporters view him as a symbol of resistance to one-party dominance, while critics point to corruption convictions and question his distance from everyday Bangladeshi life.

The election comes under an interim administration led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, which assumed power after Hasina’s ouster and barred the Awami League from participating — a decision that has sparked controversy and raised questions about the vote’s legitimacy.

Adding emotional weight to the contest is the recent death of former prime minister Khaleda Zia, a towering figure in Bangladesh’s political history.

First-time voting — but not for everyone

Following years of campaigning, Bangladeshi authorities expanded overseas voter registration, allowing expatriates to vote remotely. Officials say more than seven million Bangladeshis abroad have registered, around 5 percent of the total electorate.

Yet participation in the UK remains relatively low. Just over 32,000 Bangladeshi citizens have registered to vote, despite census figures showing more than 600,000 people of Bangladeshi heritage living in England and Wales.

The reasons are complex. Voting eligibility requires Bangladeshi citizenship and a national identity card (NID), which many British-born Bangladeshis do not possess. Others cite bureaucratic hurdles, biometric registration requirements, digital applications and limited outreach from authorities.

“For older voters especially, the process is intimidating,” Noor said. “If something goes wrong with an app, there’s no clear support.”

Younger British Bangladeshis often feel even more disconnected. Many say their priorities lie firmly in the UK, where issues such as housing, employment and British politics feel more immediate.

“We live here,” said one young woman shopping in Whitechapel Market. “What happens in Bangladesh doesn’t really affect us day to day.”

Engagement varies across the diaspora

Participation rates highlight stark contrasts within the global Bangladeshi diaspora. In Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, overseas voter registration is far higher. Analysts suggest this reflects different realities: migrants in the Gulf often maintain close economic and family ties to Bangladesh, while those in the UK and US are more settled with permanent lives abroad.

Still, some UK-based Bangladeshis remain deeply invested. Many arrived decades ago, lived through the Liberation War, military rule and disputed elections, and retain Bangladeshi passports.

At a small cultural centre on the Isle of Dogs, older residents spoke of cautious optimism. Some have already cast postal ballots, describing the election as a rare moment of hope after years of political stagnation.

“I waited a long time for this,” said one woman who last voted in Bangladesh more than 30 years ago. “Now it finally feels like my vote matters.”

Others are more sceptical. A 23-year-old student in East London said he chose to boycott the election, arguing that banning the Awami League undermines democratic credibility.

Britain’s political shadow

Britain’s significance in Bangladeshi politics is underscored by the presence of influential figures on both sides. Tarique Rahman’s long residence in London remains controversial, while Tulip Siddiq, a Labour MP and Sheikh Hasina’s niece, was recently sentenced in absentia by a Bangladeshi court — a move criticised by UK-based legal experts as politically motivated.

Several UK-based local councillors of Bangladeshi origin are also standing in the election, raising questions about dual loyalties and accountability. Although Bangladesh permits dual citizenship in practice, constitutional rules restricting foreign citizens from holding office remain poorly understood.

Hope mixed with uncertainty

Across East London, conversations about the election reveal a community divided by generation, experience and expectation. For some, the vote represents a long-overdue chance for political change. For others, years of broken trust and bureaucratic barriers have fostered apathy.

Ultimately, daily life in Britain — work, family and security — continues to outweigh distant political struggles for many. Yet the election’s emotional pull is undeniable.

“If change doesn’t happen now,” said one middle-aged resident, “then when will it ever happen?”

.svg)